Female workers of the world, unite. Battle for equality in the age of subtle sexism08.03.2019

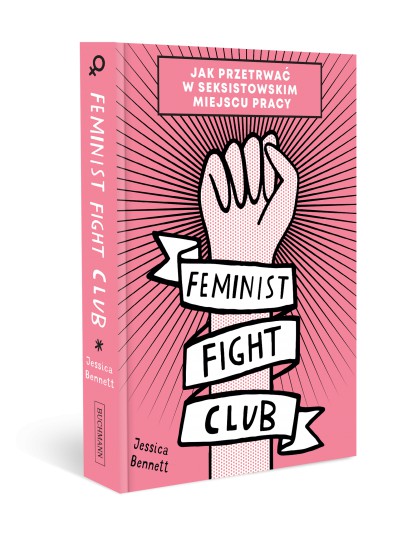

Do women of the 21st century still need to fight sexism at work? Jessica Bennett, author of "Feminist Fight Club. An office survival guide" insists that they do – and that they should use war rhetoric to do so.

In Poland, “feminism” is often considered a dirty word. Many of my friends, all progressive, well-educated and successful in their chosen careers, are reluctant to call themselves feminists. While they support women’s empowerment and gender equality, they say that in Poland this term has such negative connotations, that they would think twice before describing themselves as such. My 25-year old sister said she sometimes avoids using this word, just because she cannot be bothered to deal with the discussion that would surely follow.

Jessica Bennett, the author of “Feminist Fight Club. An office survival manual”, chooses exactly the opposite strategy. The choice of words matters, and Bennett decided to employ war rhetoric – while describing sexism at work. In her book, she calls different types of sexist men “enemies”, and the workplace “a battlefield”. Isn’t she afraid of the counterproductive effect? Her reaction to this is swift and strong: “I find it hilarious when people ask me this question. Would anyone ask this if I were a man?”

I think that women are often asked to be “nice,” to use nice language, to talk about the fight for equality in a way that is about “empowerment”, not battle. But this is in fact a battle on multiple fronts.

For Bennett, the point of using war rhetoric is to turn the male trope and extremely masculine language on its head – “both because this IS a battle (albeit not a physical one) but also because it’s funny”.

And it is true that the book is funny. It reads like a manual for millenials, filled with minimalist, black-and-white illustrations, catchy phrases such as “The Menstruator” and “The Himitator”, and tips on “how to smash the caffeine patriarchy”. But beneath the funny surface, the subject matter is extremely serious. Bennett explains: “One of the things I tried to do with this book is use humor as a way to open up a conversation that often people are uncomfortable talking about – and the battle/war metaphors as well as the silly names for “the enemy” are examples of this. But in general, I think that women are often asked to be “nice,” to use nice language, to talk about the fight for equality in a way that is about “empowerment”, not battle. But this is in fact a battle on multiple fronts – why not call it that?”.

Facts seem to support Bennett’s words. Although times are changing, and blatant, in-your-face sexism is deemed less and less acceptable, there is still a lot of work to be done. Although the wage gap between men and women has narrowed, it is as real as it was 15 years ago, and women are still underrepresented in top corporate, professional and political positions. And this persists despite the fact that women are increasingly better educated than men. According to the European Commission, women amount to less than ⅓ of board members of the European media – even though ⅔ of journalism graduates are female! The situation is even bleaker in Poland, which is the 4th worst country in terms of number of women in positions of power in media.

In 2010, when Bennett was a junior reporter at Newsweek, she encountered sexism for the first time. She learned that the women of Newsweek sued the company for gender discrimination forty years prior, in 1970, because of disparities between them and their male colleagues. This was Bennett’s awakening. Before that, she says, she was loosely aware that sexism existed, “but I also think that to some extent my upbringing – by very progressive parents, who always taught me I could accomplish whatever I set my mind to, and then college where women did in fact outpace the men – did not prepare me for the real world. It was at Newsweek, as a junior reporter, that I really first became aware of sexism and began calling myself a "feminist".

This stuff is not rocket science, but sometimes it needs to be said. Promote women. Mentor women. If you’re booking a panel, make sure it’s not men [only]. And don't just sit around talking about diversity.

The media world had come a long way since those early days at Newsweek – but not far enough. Bennett recalls realizing in 2010, forty years later, that many young female reporters were still making less than their male peers. As the first-ever gender editor at the New York Times, Bennett describes her obligation to advocate for other women: “This stuff is not rocket science, but sometimes it needs to be said. Promote women. Mentor women. If you’re booking a panel, make sure it’s not men [only]. And don't just sit around talking about diversity -- recruit for it, set targets for it and make sure you’re interviewing as many women as men for jobs.

As the gender editor, Bennett is not in charge of any particular section of the newspaper. Rather, her responsibility is ensuring that the gender aspect is present across all NYT’s coverage. “In journalism particularly, diversity and gender parity must come from all angles. It’s about staffing and leadership positions, yes, but it’s also about who we cover, how we cover them, sources we quote, images we pair with stories, and of course bylines. As gender editor, I’m thinking about all these things, and also how we can better engage with a global female audience”, she explains.

Women have to fight subtle sexism at work all the time, and as confirmed by a recent report by Harvard Business Review, because of its very nature of ambiguity, subtle sexism is doing more harm than blatant discrimination. It is hard to fight something that you cannot really pinpoint yourself – when you feel that something is wrong, but can’t really define why. Benett describes it as: “that persistent double standard, that damned if you do, damned if you don’t, speaking softly when they’re trying to talk loudly, trying to cut the sorrys while still sounding modest, avoiding “I feel like” but still speaking in a nurturing tone. Easy, right?!”. And the ambiguity of the subtle sexism makes it more difficult to seek remedy for it – legal, administrative, or simply human, like telling somebody off without being accused of overreacting. The result? Women are afraid to ask for a raise or a promotion, and are often eager to give away credit for their work to somebody else – most likely men.

Women who are assertive are penalized for being too “aggressive”, but those who are not are deemed too “soft”. Women should not have to “behave like men” to get ahead – but the reality is that as long as there are so few women in power, these traits will continue being thought of as “male” or “female”.

In my professional life, I have often encountered successful women that behaved in a harsher manner than men in similar positions, and unofficially said that they felt obliged to do so – in order not to be accused of being too «nice» and «unprofessional». Is there another way, or are women doomed to play «men’s game» in order to survive? According to Bennett, it is a double-edged sword. “Women who are assertive are penalized for being too «aggressive», but those who are not are deemed too «soft». Women should not have to «behave like men» to get ahead – but the reality is that as long as there are so few women in power, these traits will continue being thought of as «male» or «female». The reality is that men and women lead in all different kind of ways, but it’s going to take having equal representation for us to start seeing the nuance. My feeling is we need more women in power to normalize the female leadership style – so that whatever way a woman leads, it’s representative of HER as a leader not her as a representative of her gender”.

One of the most common displays of subtle sexism is men telling women to “smile, darling”. And while it is not something that you could sue somebody for, it is simply very annoying – especially when you are having a bad day. Bennett’s advice? “I reply that I have resting bitch face, have they heard of it? It’s a clinical condition (not really). Or I employ a method that the actors in «Broad City» – a hilarious and popular comedy sketch show here about two best friends navigating NYC – invented: you put each of your middle fingers to corners of your mouth, and then curl upward”. As easy as that. But this method, as well as Bennett’s book in general, might prove controversial in a country, where educated, well-off, urban young women are reluctant to call themselves feminists.

Bennett finishes her book with a call to all men, entitled: “How To Have a D*ck Without Being One”. She writes: “You, men, are crucial to this battle. We need you on our team…. Winning this battle doesn’t mean you lose. This isn’t a zero sum game. Until the robots take over, you need us, and we need you to keep this whole life thing going. Also: liberating us means liberating you: making your companies more profitable and cooperative, us earning more money so that you don’t have to, raising kids who grow up to be healthier and more confident because they have working mothers and engaged fathers, and helping you make smart decisions at work”.

And this is something that is easily lost amongst the war rhetoric and funny names: this battle is a common one, and with a shared goal of a better world (for men and women). Without the support of male troops we will not be able to win it.

see also

- New Meanings. See the Music Video for Wicked Game by DJ Duo Yola Recoba Papaya Films

News

New Meanings. See the Music Video for Wicked Game by DJ Duo Yola Recoba

- Myriam Ballesteros: Don’t be afraid of failing

Papaya Rocks Film Festival

Papaya Rocks Film FestivalPeople

Myriam Ballesteros: Don’t be afraid of failing

- Can Skrillex Songs Be Used as Insect Repellent?

News

Can Skrillex Songs Be Used as Insect Repellent?

- The 2019 Papaya Young Directors Competition Has Launched Papaya Young Directors

News

The 2019 Papaya Young Directors Competition Has Launched

discover playlists

-

Nagrody Specjalne PYD 2020

02

02Nagrody Specjalne PYD 2020

-

Papaya Young Directors 5 Autorytety

12

12Papaya Young Directors 5 Autorytety

-

John Peel Sessions

17

17John Peel Sessions

-

Original Series Season 1

03

03Original Series Season 1