Kornél Mundruczó: The Most Melancholy City on Earth07.12.2018

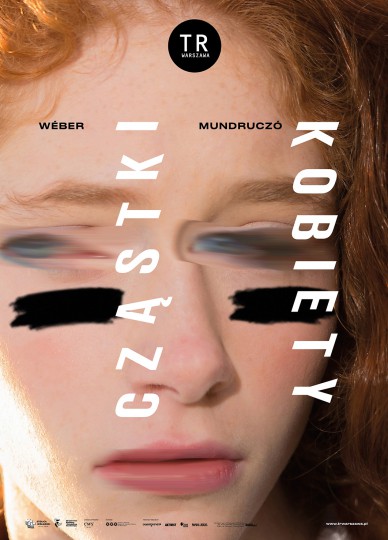

“Under this system, you either practice art for art’s sake, or you end up becoming a jester for the government,” says Hungarian director Kornél Mundruczó whose new play Pieces of a Woman will premiere in TR Warszawa on December 13.

Budapest is drowning in chaos, and the locals feel lost and trapped. Thousand of refugees are streaming into the city from the East, but nobody really has any idea what to do with them. The tension seems to ratchet up with each passing day. As the movie reaches its climax, the Keleti railway station is blown up with a bomb.

These are fictional events, obviously, but only to an extent. In Kornél Mundruczó’s latest effort, Jupiter’s Moon, the migrant crisis is brought to a violent conclusion in the form of the fictional bombing, but the real-life situation at the peak of the crisis was at least as volatile, while for the thousands of people fleeing the flames of war spreading across the Middle East, Budapest’s Keleti station became a shelter, a refuge, and a beacon of hope, but also a dead end that seemed to imply that safety from suffering would remain beyond their reach.

“I tried to capture the atmosphere of 2015 Hungary. It was all chaos, all madness. Nobody knew what to expect, people felt lost and trapped. This state of confusion and uncertainty is reflected in camera direction: to the viewers, the camera moves in mysterious and unpredictable ways. The purpose of the story the film is telling, however, is to paint a broader picture of the situation – particularly the pervasive sense of confusion and loss that has become so typical for this period we live in. And I’m not talking about just Hungary here, I’m talking about the whole of Europe. I’m a devoted fan of Aleksei German. Although at first glance German’s films, like My Friend Ivan Lapshin or Khrustalyov, My Car!, may seem just run-of-the-mill stories, at their core they are first and foremost a penetrating examination of the Stalinist era.

The Hungarian director is a tireless storyteller. The narratives he weaves in his films or plays are often bizarre, balancing somewhere between realism and fantasy. This surrealist shift, however, allows the director to better flesh out the evil or the absurdity of the here and now. His multiple award-winning 2014 film White God is a story of homeless dogs rising up against their human oppressors. Below its fantastical skin, however, lies a bitter satire on contemporary Hungary, Europe, and the world in general. Using the struggle of dogs against men, Mundruczó ridicules our eagerness to endure manipulation dealt us by politicians and the unthinking ease with which we can embrace racially-motivated slaughter. In White God, mixed-breed dogs are cast out on the street en masse only because the authorities decided to impose unreasonably high taxes on their owners. The mongrels are then rounded up by dog catchers and slaughtered. But the humans are unwilling to contend with the unfolding mass canicide—instead, they bury their thoughts in work or their own problems, tacitly satisfied with not having another “burden” to deal with.

“The rise of nationalism and the populist right that we’ve been witnessing over the past couple of years in Hungary and across the globe, is not exactly new, nor is it driven by some novel, heretofore unknown factor or force. It’s still the same old capitalism, but this time even more insular than before. Tribal and national, putrid, sad, and corrupt, like Communism in the late 1980s, when even communists themselves could no longer believe in it.”

Kornél Mundruczó, born in 1975, considers himself a member of Generation Zero. “My early years were spent under Communist rule, but does not mean my memories of that time are necessarily bad. Hungary was pretty well-off back then, there was no widespread repression. What I do remember is the amount of free time we had as kids. The world around us seemed strangely immutable, while the time that we had so much of did not seem to move forward at all, everything seemed to be standing still. Every year was just like the last one. Our lives seemed unchanging, we were certain that nothing would ever be different, or at least nothing would change for the next couple of decades. Life really seemed okay—everyone around had a car, we all spent summer breaks on the shores of the Balaton, we had a little more money than the rest of the Soviet Bloc, and there were no gasoline shortages. It was nothing special, but struggling against the system just wasn’t worth it; it was clear to us that fighting wouldn’t change anything and that no one truly had any influence over the shape of things. Besides, this immutability of our existence and the impression of being in stasis, so to speak, offered a peculiar sense of security. For a child, that meant that instead of a multitude of temptations, the world offered us space where our imaginations could roam free. The 1990s, on the other hand, were the inverse of the world we’ve known before, suffused with euphoria and unchecked freedom. To me, on the other hand, it was first and foremost an era of wild, unbridled avant-garde. All the old limitations we’ve been subject to have disappeared overnight and artists across the former Soviet Bloc still had no idea of the new barriers that waited ahead, so the freedom we experienced felt limitless. And those films! Early von Trier efforts, Wong Kar-wai. This was a revelation, a sign of what was to come. But it all fell apart after 2000—the enthusiasm and maniacal creativity burned out, but the brutal capitalism remained. It became apparent that we were living in a world devoid of ideas and values, where young people were taught only that they should get rich and lead comfortable lives, nothing else.”

Family relationships, particularly the bonds between parents and their children, are a recurrent theme in Mundruczó’s films and theater plays. In White God, a teenager’s love of her dog (and of music) ends up saving the world (and the dogs’ lives), but even more important is the fact that it opens the eyes of her father who finally realizes that in pursuit of conformism he allowed himself to become a hostage of the authorities. Likewise, in Jupiter’s Moon, the love a son has for his father serves as a counterpoint to the chaos that seems to engulf the world, while the relationship between mother and daughter underpins his latest stage effort, Pieces of a Woman, set to premiere December 13, 2018 at TR Warszawa.

Everyone has their own peculiar bond with their parents. I’m profoundly fascinated by their dynamics and the fact that they always seem to be based around some form of social compact. Additionally, I often tend to veer off the beaten paths, and end up creating strange, abstract narratives.

“Pieces of a Woman grew from a brief text I found in a notebook belonging to Kata Wéber, a writer I have been collaborating with for years. It was a fragment of a conversation between a mother and a daughter. The passage left me stunned. I began pressing Kata to develop it into something bigger. And she did, she spun it into a drama piece. The relationship between a parent and their child is a rather universal subject, so I often build my stories around that particular theme. It’s something everyone can easily relate to, everyone has their own peculiar bond with their parents. I’m profoundly fascinated by their dynamics and the fact that they always seem to be based around some form of social compact. Additionally, I often tend to veer off the beaten paths, and end up creating strange, abstract narratives. And in this case family serves as a sort of anchor, it’s something familiar and recognizable, something the audience may latch onto, something that needs no exposition.”

Pieces of a Woman are the second collaboration between the director and TR Warszawa. The previous effort, the 2012 play The Bat, was enthusiastically received by critics and audiences alike. The play, a bold amalgam of diverse genres meandering between grim seriousness and operetta-like glee, has received a number of awards, including the main prize that the Divine Comedy International Theater Festival in Krakow.

“An excellent cast is a priceless instrument in the hands of a director like me. I’m not one to direct their every little move. On the contrary, I give my actors considerable leeway and simply observe the direction they move in. For quite some time during the prep work on The Bat I wasn’t giving the actors any pointers at all. Instead, I waited to see what they themselves would come up with. We’ve embraced a similar approach this time, too, the only difference being the three-week-long workshop on family relationship I had the cast go through before they ever set foot on the stage. They drew their family trees, everyone had to play their own mother, reenact the first encounter between their parents. In the course of those three weeks, we managed to accumulate some penetrating insights on memory, childhood, and the shapes of apartments and dwellings we lived in.”

About his own family, the director says briefly – it’s normal, exceedingly so. “I was loved and supported by my parents, which always gave me a lot of peace and a considerable sense of independence. On the other hand I remember how surprised my father was when I called him to say that I was accepted into the Budapest film and theater school. He said: ‘You? In an arts college?’ This was so disarming, I guess he truly did not expect me to make such a move. There were no artists in our family before me.”

I don’t really know whether I’ll be making any more movies in Hungary. On the other hand, I can’t imagine living anywhere else than Budapest. It’s the most melancholy city on Earth.

In Mundruczó’s opinion, the situation of artists living and working in Hungary has become quite dire. “Personally, I have yet to experience censorship, but that may be a byproduct of my position. Simply put, I’m hard to say ‘no’ to. But I know for a fact that censorship’s ramping up across the country. Truth be told, life in Hungary has become rather difficult. The opposition is practically nonexistent, unless you count the government-sanctioned opposition which has been set up only to provide the regime with a boogeyman. Naturally, you have to take up some sort of position on these things, because life becomes unbearable otherwise. For a time, I was certain that I succeeded in the effort, that I kept gaining a better understanding of the system and could speak about it openly. But then I realized that I was merely a jester. As an artist, you either practice art for art’s sake, ultimately a futile pursuit, or you become a jester for the government. And I think I became such a fool. I lend credibility to Orbán, entrench the more hardline policies, keep erecting monuments to the regime. I don’t exactly feel comfortable with that, so I don’t really know whether I’ll be making any more movies in Hungary. On the other hand, I can’t imagine living anywhere else than Budapest. It’s the most melancholy city on Earth.

see also

- The Beatles: Get Back: See the Exclusive First Look at Peter Jackson’s Documentary About the Band

News

The Beatles: Get Back: See the Exclusive First Look at Peter Jackson’s Documentary About the Band

- Films of Future Past

Opinions

Films of Future Past

- An Aerographite Spaceship Could Reach Proxima Centauri in Record Speed

News

An Aerographite Spaceship Could Reach Proxima Centauri in Record Speed

- Announcing the winners of the 2nd Papaya.Rocks Film Festival Papaya Rocks Film Festival

News

Announcing the winners of the 2nd Papaya.Rocks Film Festival

discover playlists

-

03

03 -

Nagrody Specjalne PYD 2020

02

02Nagrody Specjalne PYD 2020

-

Papaya Films Presents Stories

03

03Papaya Films Presents Stories

-

Cotygodniowy przegląd teledysków

73

73Cotygodniowy przegląd teledysków