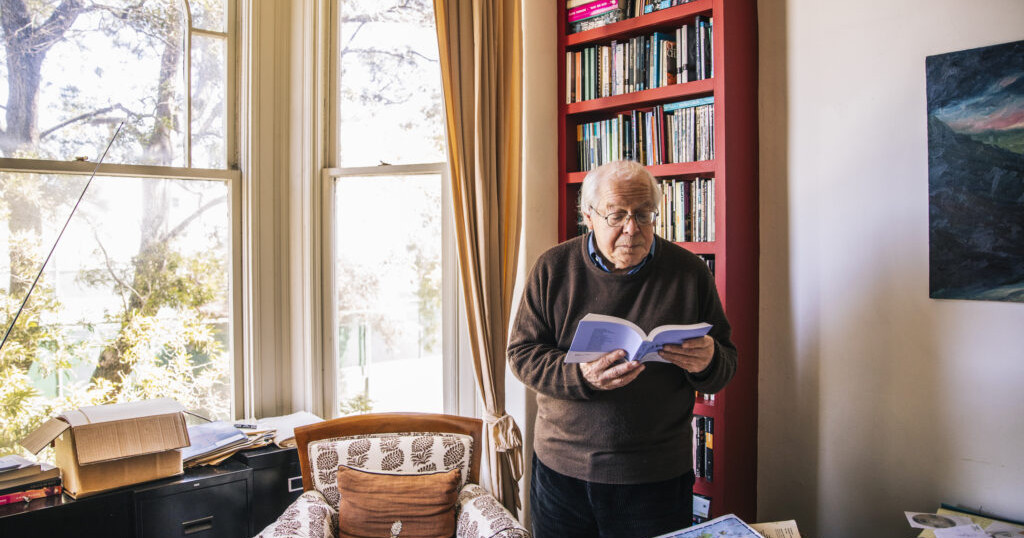

“We love watching disasters… as long as they do not happen to us”: An Interview with David Thomson 24.06.2022

David Thomson is considered one of the greatest film critics of his generation. He has written about 30 film books written and published articles in the world’s most renowned magazines such as "Sight and Sound", "Film Comment" or "The New York Times".

In 2019, he published Sleeping With Strangers: How the Movies Shaped Desire. It’s a condensed, anecdotal book about desire in the cinema – it links both academic writing and journalistic insight. Interestingly, it is also one of the rare occasions in which Thomson decides not to talk only about the movies but also about his personal life. A few months ago, Thomson wrote a much more philosophical book. It is called Disaster Mon Amour, and it describes various versions of disasters that for the centuries affected humanity in different ways. With well-known wit, Thomson tries to make something out of the disasters (including COVID-19). This book can be considered as something new (its narration is experimental) in his already rich bibliography.

You are probably one of the most recognizable film critics in the world. Did you achieve everything you have always wanted?

No! I am horrified at the thought that anyone might have achieved everything they wanted. I contend with a whole lot of things, unfinished or incomplete. Not to mention everything I have never done and would love to do, like going to India or reading many books that still await me.

Do you find it somehow frustrating?

I feel some kind of regret due to the list of undone things, but there is nothing I can do now. I am aware of the fact that the job “is never done”, but I have accomplished plenty of other things. And that is something for me. However, I have also made a ton of mistakes. All that teaches you that life is a rollercoaster of many chances and coincidences. You never know what happens, and you are never really sure when your choice actually matters.

What in your view made you successful as a film writer?

It took me some time to realise that the thing I could do best was to write about the experience of seeing a film, and that it might be a form that is able to entertain other people. Everything I have done since then is just trying to “change” people’s life by recommending them titles they might have never heard of. And when someone sees the film, he/she might go back to what I have written and find my writing helpful. It might untangle the viewer’s feelings about the particular film. I am not interested in revealing the plot of the film – I prefer to write about the feeling of “being” with the movie. If I had any success, it is because I can crystalize the emotion the viewer might have in the audience. Thanks to my writing, the thoughts or emotions about the films are becoming clearer for people.

There is also something else: I just love writing. Mostly about the film, because more or less I was able to earn a living by doing that. But it might have been something else. For instance, I am very enthusiastic about the sport. I know a lot about this field, and if the film did not exist, then I would very happily write about sport in general. Or, alternatively, I have always dreamed of writing a book about weather. Not the weather in the sense of global warming and the huge crisis, but just everyday weather. How does it affect us, and what is our approach towards it. I will never do it, but you see my point: I have to write to survive.

In your writing, you are not only playing with words but also with humour. Your readers are always indicating your wit, which you notoriously use when writing about films. Did you have to develop it over the years?

My father and I did not get on well, but one thing about him that I admired was the fact that he loved to tell jokes. In my eyes, he was becoming a better person because he always wanted to make people laugh. His dry, intelligent humour was a huge part of my upbringing. When you meet someone for the very first time, there is a natural nervousness – and thanks to my father, I am no longer shy; I want (and I need) to make people laugh. It breaks some sort of reserve, it warms up a room a little bit. Although I would never try it by myself, I understand the impulse that forces people to become comedians. I believe that making people laugh is a wonderful gift; some do it professionally – like Charlie Chaplin – and others do it in life. If you are in the business of telling jokes, you learn that some lines do not work (we all have been there), but sometimes there is a huge sense of joy when you feel someone’s laughter as a response to something you have just said. And the bond grows between you two.

Cinema legitimized the desire – we are talking about the times when talking about sex became more possible, and I believe that the movies were a cause

What is the story behind the main topic of your last book, Sleeping with Strangers: How the Movies Shaped Desire”? You wrote that your publisher suggested it to you, but I get a sense that the story has some sort of a broader context.

It was a publisher’s idea, but I quickly took the idea and rearranged it a little bit. Thanks to photography, and then even more by the cinema, we were taught that some faces were desirable. Cinema legitimized the desire – we are talking about the times when talking about sex became more possible, and I believe that the movies were a cause. What is more, I do not think that the whole process of gay liberation and the enlightenment of the world towards the gay experience could have happened without the movies. Because the films were a medium like nothing ever before. They said: “look at this story, look at all those actors; whatever gender you are, you can adore whomever you like on-screen.” And it had fantastic consequences: it made the lives of a lot of people more interesting, exciting. I am not saying that the cinema is the only factor that influenced the 20th century gay liberation, but I think it was vital to it. The chief purpose of that book was to elaborate on that idea. However, there is still a long road ahead. If we look at America right now, we can perceive that there are still a lot of things that need to be settled between the groups supporting and not tolerating LGBTQ society.

And what about Disaster Mon Amour, your newest book? Its title draws from the critically acclaimed film Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959).

That book grew out of the experience which I had in 2015. I watched the film called San Andreas, which is not any respectful thing, but it is brilliantly made at the level of CGI. It is basically about the catastrophe of earthquakes: I saw the film in the packed theatre in San Francisco, and the audience was wild with excitement! When our city was torn apart by the earthquakes, the audience cheered, laughed, and shouted! And yet, they knew that the on-screen fantasy was actually a threat they lived with literally every day. I was here in San Francisco in 1989 when the earthquake affected all of us; maybe that is why I was fascinated that these people could laugh at it.

Did you find out why they were reacting in such a way?

Disaster seems like an ominous thing which we all want to avoid, but we love watching it when it is happening to other people. Even now, at this terrible moment in our history, when we see imagery from Ukraine of devastation (and we feel helpless), there is something of entertainment in that. It is very dark, it gets deep into the way in which we will love to watch other people have a bad time… as long as it does not happen to us. I was fascinated by it. Obviously, I wrote the book long before Ukraine happened, but I can see a correlation here. We live with this ambiguous attitude to what we call “a disaster.” It is a book on all kinds of disasters: it covers everything from the concentration camps to slipping on a banana skin. It reveals that we, as human beings, do not have an adequate sense of proportion towards disasters in our lives.

Even today we are scared about the Nuke, we are scared of Russia, and that is why we do not intervene. We just, night by night, watch our televisions… and we watch the footage, we watch and watch all the time. And we do nothing! We are just getting used to the violence that surrounds us

Furthermore, Hiroshima Mon Amour was – both as a film and a title – something that has always fascinated me. It is a love story taking place on the side of what was left of the disaster in 1945. And Hiroshima was one of the worst disasters of all time! Although, it was a disaster that people believe “has ended” the II World War. Once again, I can sense some sort of ambiguity in this narration. Even today we are scared about the Nuke, we are scared of Russia, and that is why we do not intervene. We just, night by night, watch our televisions… and we watch the footage, we watch and watch all the time. And we do nothing! We are just getting used to the violence that surrounds us.

Both books consist of your personal input. In Strangers, you admit to having an affair; in Disaster, you go back to the recent situations in your pandemic journal. In your previous books, the reader could not see such exposure. Why?

Probably I am just getting older. For a long time, I taught as a Professor of Film Studies, I wrote about films, and I always tried to stay “objective,” as the unwritten rule states. After that, I just felt I wanted to write what the film meant to me and to reveal how exactly I was shaped by the experience of watching that exact movie. There is an extraordinary condition in watching the film when you are sitting in the dark, in safety and security, and you are watching – on the screen – these amazing, sometimes even miraculous things, which might even save your life. Sometimes they are lovely, sometimes they are terrible. But they always influence you! You watch it with all your fantasies, and the worst feeling is probably the fact that you cannot get into the screen. And, paradoxically, you are later gradually trained to objectively review something that you cannot intervene with.

I believe that definition of spectatorship is at the heart of a lot of our political dilemmas. We all feel that we can watch everything and yet have no part in it. These concerns interest me today even more. And, again, there is some sort of ironic humour in that. But it is still terrible. Because of that, I do feel that people are made ill watching Ukraine and the whole suffering because it is just like watching the film – you receive the image, but there is nothing you can do. You cannot interfere. It is a really alarming feeling. Once again, I am letting in my personal feelings, but what can I do, I am just a human being. For a long time, I believed that people doing what I did should write about film in terms of “how it was done”. I feel an increasing need to talk about what the films are. What are they saying about our experience? About us? To answer these questions, I cannot keep myself out of it. That may trouble or offend some people, but if I want to do it, I have to do it this way.

see also

- Do Nolan Films Have a Sound Mixing Problem? Director Addresses Complaints

News

Do Nolan Films Have a Sound Mixing Problem? Director Addresses Complaints

- Download a van Gogh on Your Phone

Trends

Download a van Gogh on Your Phone

- First Gym for Esports Athletes to Open in Tokyo

News

First Gym for Esports Athletes to Open in Tokyo

- Genesis Under a Microscope

News

Genesis Under a Microscope

discover playlists

-

George Lucas

02

02George Lucas

-

Nowe utwory z pierwszej 10 Billboard Hot 100 (II kwartał 2019 r.)

15

15Nowe utwory z pierwszej 10 Billboard Hot 100 (II kwartał 2019 r.)

-

Papaya Young Directors top 15

15

15Papaya Young Directors top 15

-

Muzeum Van Gogha w 4K

06

06Muzeum Van Gogha w 4K