Łukasz Żal | A Companion in Indulgent Fantasizing12.04.2019

Łukasz Żal is currently one of the most sought-after cinematographers in the world, and his talent has been acknowledged by the movie industry: he’s been recognized by the American Society of Cinematographers, he’s received the Silver Frog at the Camerimage Festival, and has been nominated for a BAFTA, the Golden Lions, and twice for the Academy Award. We’ll be speaking about the jealousy which made him pursue filmmaking over photography, and why he doesn’t do small talk on set.

It’s June 2014. At the Koszalin Festival of Film Debuts, Malte Rosenfeld steps onto the stage to receive an award for Best Cinematography for Little Wires. Footage from the festival for the Weekend Movie Magazine is shot by Łukasz Żal. The cinematographer is still nursing a limp from a recent, barely healed leg fracture. A couple of months before, Żal has been contacted by Irek Grzyb, the director of Little Wires, who offered him the DP job on the film, but Żal refused, satisfied with the commercial work he was doing and the income he was pulling in from renting out his high-grade camera. Soon after he was able to pool enough money to buy his dream car—a Land Rover Discovery. The car was available somewhere outside Łódź, where Żal lived at the time, so the filmmaker took a car mechanic to advise him with the purchase, borrowed his brother’s car and set out to complete the buy. But they never made it—a crash en route left Żal with two fractured legs and the mechanic with minor injuries; Żal also had to buy a car for his brother to replace the one he’d totaled.

“I lost all my savings and the recovery has been a long and painful process. And that job for the Weekend Movie Magazine was the first gig I managed to score after nursing myself back to health. At the time, I truly felt as if a higher power wagged a finger in warning at me.”

Videotapes for Insomnia

Łukasz Żal is currently one of the most sought-after cinematographers in the world. Just last year, his work on Paweł Pawlikowski’s Cold War brought the Łódź Film School graduate his second Academy Award nomination and an award from the American Society of Cinematographers. Żal was also nominated for a BAFTA and the Golden Lion, and received a Silver Frog at the Camerimage Festival. His upcoming projects include a collaboration with Netflix and the legendary screenwriter and director Charlie Kaufman on the film I’m Thinking of Ending Things.

Before discovering a love of the cinema in high school, Żal sought other ways of expressing himself. Back in his hometown of Koszalin, he wrote for his high school paper and even managed to get a handful of short stories published in the Głos Pomorza. One summer break, he got an internship at “Bryza,” a regional broadcaster that dealt mostly with West Pomeranian matters. He got the internship through the father of one his high school friends—the boys’ parents wanted to motivate them and find them something to do throughout the summer.

“The truth is, I was a bit of a hellraiser during my high school years. My father went as far as pay money for me to get that internship. The local TV didn’t have any money for wages, and you had to be paid for work rendered. So my dad gave them 1,000 PLN so they could then pay us that same amount.”

One day, Żal discovered the Koszalin mediatheque and its rich movie collection. He began watching one film after another, taking in as many as three flicks per day during his more intense binges.

“I would pick up three Herzogs and return them the next day. The guy who worked there soon noticed that I was dropping by every single day and started giving my recommendations, suggesting Fellini, Polański, Bergman, Antonioni. So I would pick those up and spend night after night watching them.

Twelve Hours of Meditation

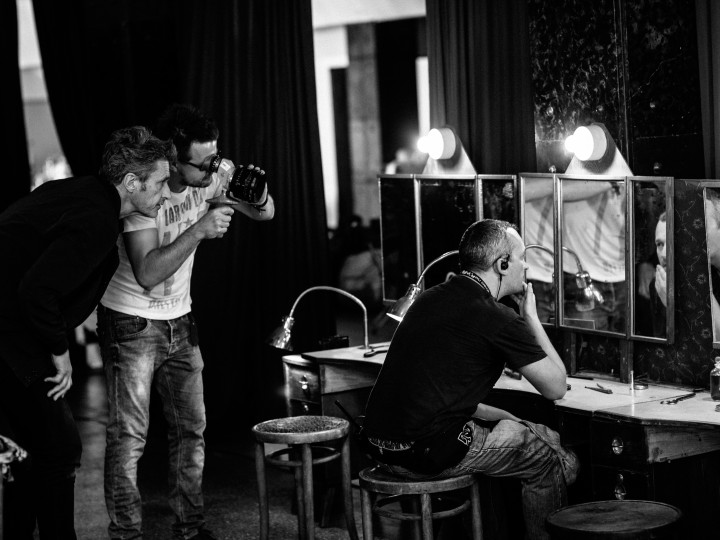

Before shooting Ida and Cold War, he lenses a couple of documentaries, including Piotr Bernaś’s Paparazzi and Aneta Kopacz’s Joanna, which was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Short Subject Documentary. Żal Says that the unceasing mindfulness he likes to practice on set is rooted in his experience with documentary filmmaking.

“Shooting a documentary, you become a part of the world you’re filming. What you do is often a product of the attention you’re capable of giving to a subject, of how well you’re able to predict when to turn the camera on to capture relevant words or situations. Shooting features is similar. When I was working on Ida, I noticed that if I allowed myself even one relaxing conversation on set, I’d invariably end up running into some nasty surprise down the line. So I began pushing myself to levels of focus I’ve never experienced before. I’d go as many as twelve hours thinking about one single thing, it felt like meditation. I was fully attuned to whatever was going on around me and constantly thinking whether there was still something I could do better.”

Initially, Żal was only supposed to be a camera operator on Ida. Although the operator indeed carries the camera and operates it, the don’t actually make any final decisions on the framing and composition of the shots. But when Ida’s original DP, Ryszard Lenczewski, ran into health problems, the director tapped Żal to replace him. Pawlikowski threw him into the deep end, but Żal passed with flying colors.

I Could Never Do Anything Similar

Żal’s frames offer carefully composed visuals, and nearly every single one could easily double as a stand-alone photograph. That, however, should come as no surprise—before he became a filmmaker, he was a Żal was intensely passionate about photography. Already as a teenager he taught himself to operate his father’s Zenit camera, but wasn’t always satisfied with the images he developed. In spite of this, a friend convinced him to attend photo consultations held at the Łódź Film School. By his own admission, his portfolio was rather thin at the time and that he wasn’t exactly ready to show the world his work just yet.

“They laughed me out of the room. I had this one picture of gleaming pipework taken at some backyard or another. In mocking tones and barely holding it together, the committee began asking me whether it was for central heating or ventilation.”

He recounted that the review concluded with one of the board telling him: “There are so many wonderful things in life, Łukasz, what on Earth made you take up photography?”

Żal only secured an extramural spot in the photography program in Łódź on his third try (in the meantime studying full time at the AFA Wrocław School of Photography) but soon realized that photography would never be enough for him. One evening, he and his future wife were sitting in their Wrocław apartment, watching Tarkovsky’s Stalker on a tiny Otake television set with a built-in VCR. The cult classic tells the story about three men journeying through the restricted area known only as the “Zone.” Intent on reaching the wish-granting “Room,” they make their way through a number of locations, including a tunnel called “the meat grinder,” resembling an underground sewer system.

“I watched these sequences and felt a pang of jealousy, as I realized that I could never create a narrative so moving using photography and nothing else. I saw this machine and felt a wave of anxiety wash over me, I was horrified that if I stayed in the same place, I would never be able to accomplish what I desired most in life. I gazed around the room, looking at the pictures hanging everywhere, and began wondering whether looking at them evoked any feeling in me at all.”

A couple of months later, Żal hitchhiked from Wrocław to Łódź to complete the enrollment process at the Łódź Film School. He got in by the skin of his teeth—he was the second to last on the admissions list. But in Łódź, he quickly realized that using a video camera would let him tell the stories he wanted to tell how he wanted to tell them. In spite of that, he was a C+ student at best, mostly because his student shorts were focused on storytelling rather than demonstrating the full breadth of his technical ability.

Relieving the Director

When he starts working on a new film, everything else become secondary.

“This is a ‘time to fantasize,’ as Paweł calls it. It’s a period we use to fill ourselves with ideas. We allow ourselves to seek inspiration and references, preliminary conversations with the rest of the crew, experiments. But everything you do is framed by your work on the film. As the moment principal photography is slated to begin draws near, you need to start making specific decisions that will ultimately impact what the film will look like. The cinematographer’s primary role is to serve as the director’s companion in indulgent fantasizing. The director takes on an incredible responsibility, a heavy cross, so to speak, and it’s your job to relieve their burden however you can. Despite the fact that you carry your own, too.”

Working with the director of Ida and Cold War, he learned that filmmaking mostly happens on set, because Pawlikowski like to “write his films with a camera.”

“Once, I believed that the end result would be directly proportional to the effort I put into preparations. I still catch myself thinking that way. But recently I’ve come to realize that everything that contributes to the end result in any significant way happens on set.”

Working on Cold War, Żal often reshuffled the initial assumptions they set out with. Every morning, he met with the director on location where they were supposed to shoot that day, arriving before anyone else from the crew, and the resulting conversations often pushed their earlier ideas in new and unexpected directions. One of Cold War’s most recognizable scenes was born of that sort of evolution. In the scene, Irena (Agata Kulesza) is talking to Wiktor (Tomasz Kot), both of them seemingly with their backs to the camera, a folk song and dance group performing behind them. Suddenly, Lech (Borys Szyc) enters the frame, tearing down our idea of what we were looking at – it becomes apparent that the Irena and Wiktor were standing against a mirror, and the performance behind them was just a reflection.

“We began with a different idea, only to embrace this modified version on set, after we realized that it worked better than the original. When I read a script, some of the scenes I can imagine pretty well, others not so much. The conversation at the table, for example, I finally had to draw out on a piece of paper in order to wrap my head around it. The simplest shots always present the biggest challenge.”

see also

- Brett Chapman | Movies aren’t real until they have an audience

Papaya Rocks Film Festival

Papaya Rocks Film FestivalPeople

Brett Chapman | Movies aren’t real until they have an audience

- Announcing the winners of the 2nd Papaya.Rocks Film Festival Papaya Rocks Film Festival

News

Announcing the winners of the 2nd Papaya.Rocks Film Festival

- Papaya Films-Produced Music Video to Appear at Legendary SXSW Festival in Austin, TX

News

Papaya Films-Produced Music Video to Appear at Legendary SXSW Festival in Austin, TX

- Rare Behind-the-Scenes Footage and a Smiling Carrie Fisher. Get a Look at the Filming of "The Empire Strikes Back"

News

Rare Behind-the-Scenes Footage and a Smiling Carrie Fisher. Get a Look at the Filming of "The Empire Strikes Back"

discover playlists

-

Cotygodniowy przegląd teledysków

73

73Cotygodniowy przegląd teledysków

-

05

05 -

Muzeum Van Gogha w 4K

06

06Muzeum Van Gogha w 4K

-

PZU

04

04PZU