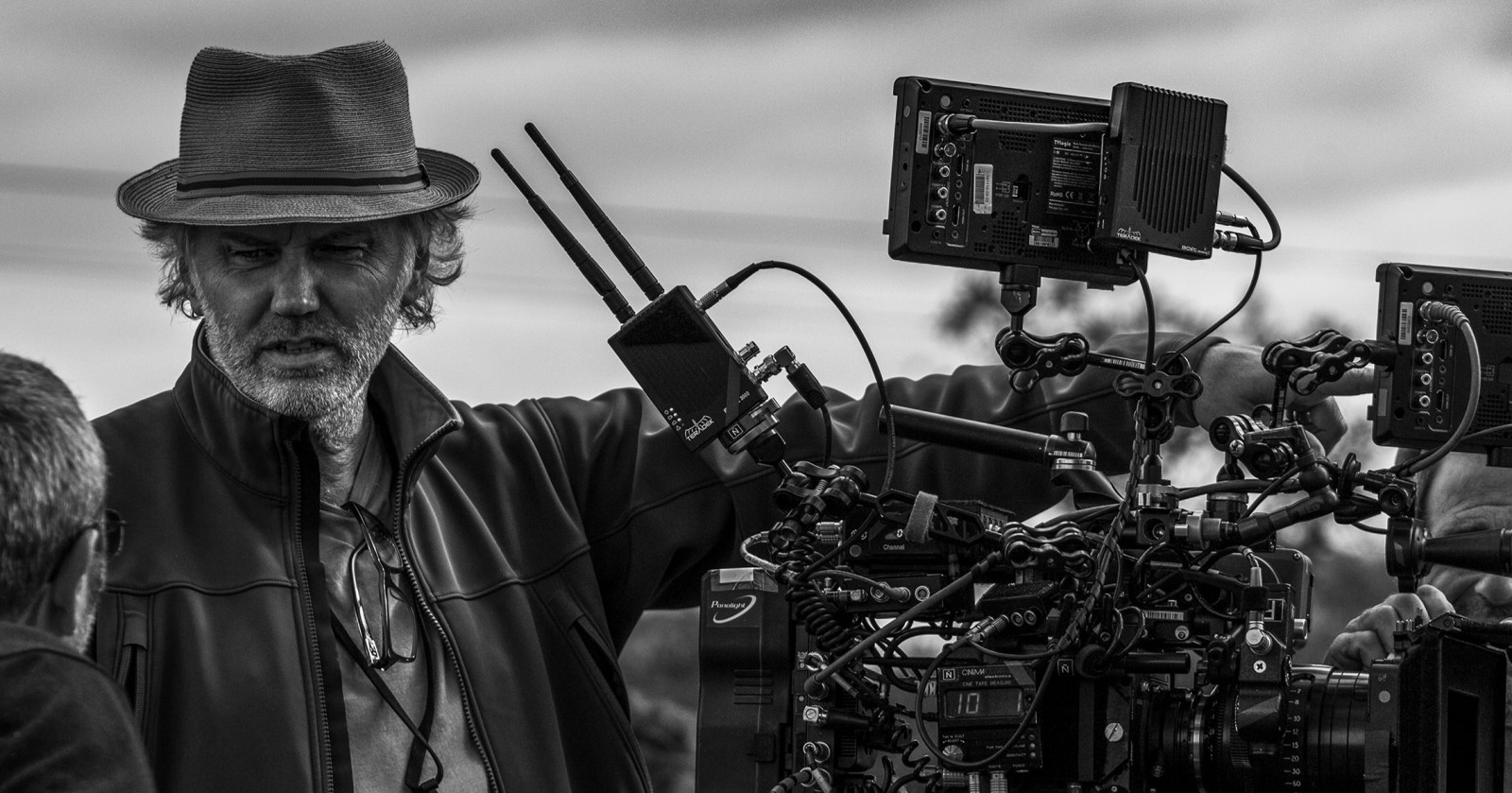

Martin Ruhe: The Soul of Movies16.04.2021

One of the most interesting and versatile DOPs in the industry. Martin Ruhe started his international career teaming up with Anton Corbijn. He worked with the director on Control (2007), telling the story of Ian Curtis, the talented and enigmatic young leader of the UK band Joy Division who committed suicide at age 23. Along with Control, Corbijn and Ruhe have worked together on many music videos, and the pair teamed up again recently for The American. He also worked as a cinematographer on Julie Delpy's The Countess (2009) and American Pastoral (2016) by Ewan McGregor. In 2018, Ruhe got a call from Grant Heslov and George Clooney asking if he wanted to join them on a new project – a miniseries Catch 22 based on the novel by Joseph Heller. Ruhe and Clooney continued working together on GC’s next movie called The Midnight Sky.

Not long ago, Martin Ruhe was announced as an honorary jury member of the Papaya Young Directors international contest. We spoke with the DOP about his background, visual inspirations, and different genre conventions.

Were you always sure you’d be a cinematographer?

Martin Ruhe: No. My family had nothing to do with the film industry and creative work. I grew up in a small town in the middle of West Germany where cinemas in the summer would mainly show old films. When I was 15, I saw Once Upon a Time in America on the big screen. It was so intense that I fell in love with it and I wanted to be a filmmaker. My parents didn’t have a lot of money so they were not encouraging this at all. I finished school, I did my military service, but I still wanted to try creating films. I went to London. There was a time when people used Yellow Pages, a telephone directory with business listings and phone numbers. So I stole a couple of pages and I looked up film production companies. I was calling everyone.

And finally, you made it?

Yes, but let’s be honest – I had no idea what filmmaking and film professions were at that time. I got a job at a camera rental in London and visited film sets whenever I could. Fortunately, there I met Mike Southon, a great British cinematographer. I spent some time with him on set, he gave me an insight. And because of him, I discovered what DOPs do. I knew that’s what I wanted to do.

How can you describe your beginnings in the film industry?

I spent a year in London, then I decided to go to a film school in Berlin which provides courses for camera assistants. At that time, there weren't many film schools in Berlin that would specifically train cinematographers. I thought that this would be the shortest way to film. After a couple of years, I started shooting music videos and TV commercials. I also made my first feature film. But the most important breakthrough of that time was the collaboration with the famous German singer, Herbert Grönemeyer. I had done some music videos for him. Anton Corbijn was his good friend. Herbert introduced me to Anton and soon enough we started working together.

Tell me a bit more about it!

I met Anton long before this when I was still studying. Anton was shooting a music video for U2 in Berlin for a song called One, and I was allowed as a guest on the set. I was standing somewhere in the corner, and I just watched and listened. Understandably, Anton couldn’t remember that. I started to work with Anton 10, maybe 12 years later. Well, as I said, I had done some music for Herbert and Anton saw them and liked the way they looked. Then I shot almost everything for Anton for 6 or 7 years.

You have collaborated with Corbijn on music videos for Depeche Mode and Coldplay, you also worked as a cinematographer on Control. It was probably a highly personal project for Corbijn.

When we started working on Control, Anton had been living in the UK for almost 25 years. He moved over to the UK because he was so touched by the music of Joy Division and other bands from that period. The most inspiring aspect for us was his personal experience. Anton has had great knowledge about the music scene of the late 1970s and early 1980s. He saw Joy Division perform, he knew the band members and their reality very well. I remember at the beginning of our work we went to Macclesfield to see the house where Ian and Debbie lived. Then we walked to the place where Ian worked. It’s a two minutes walk! That's how small his world at home was. Another thing that struck me was Ian’s lyrics. It was so deep, poetic, just beautiful. I didn’t realize how important Ian's lyrics and music of Joy Division still are to so many people.

Corbijn began his career as a music photographer, he has photographed Mick Jagger, Neil Young, Nick Cave, Miles Davis, and of course Joy Division. Someone can get the impression that you wanted to transfer the atmosphere of Corbijn’s black and white photography into a film.

When we started Control, it was Anton’s choice to go black and white. But we didn't want to look like Anton’s photographs. We didn't want to transpose his iconic pictures to film, and also we didn’t want to look like the film from the 1970s or 1980s. We decided to not go as raw and grainy as his stills, we were looking for something more contemporary.

You worked with Corbijn again on The American. This film is a tribute to the Western.

We both felt that this film was like a classic Western, so we spent a lot of time focusing on preparations. Anton and I watched some movies together. We liked Sergio Leone’s movies of course, but also No Country for Old Men. I love watching those films. I love the simplicity and straightness of Westerns, and the way they used the environment.

What was your approach as a DOP to create the aura in that film?

We tried to shoot the film as simple as possible and create a beauty emerging from where the story takes place. We chose to shoot The American entirely at the actual location, so we let the landscapes be our inspiration. Many of our shooting spots were old villages in Abruzzo like Castel Del Monte high up in the mountains. This stunning rural-Italian landscape created a good sense of isolation, and it suited our character. We spent a lot of time traveling to these places and discovering this unknown world. We used a lot of natural local colors during the daylight, but we also added some strong orange tones and deep blues at night. I love that way of filming because I get to dive into so many different worlds. That's part of why I enjoy what I’m doing so much.

Let’s talk about your own preferences – shooting on film or digital?

I don’t think it’s a principal issue for me. With digital, the process is faster, you can shoot with less light, with the cameras so much smaller, and that allows you to shoot some things that you weren't able to shoot before. But at the same time, I always loved the film. Just the smell of it was something magical, those cameras were also masterpieces. But on the other hand, the film asks for a bit more discipline. With film, we are more focused because we’re not so certain how it would turn out. When you shoot with a digital camera all these monitors surround you, people can watch everything. But when we depend only on monitors, we lose focus and details which people see later in the cinema. However, I wouldn’t fight for a film. You’ve probably seen Roma or 1917. It’s so much good art stuff that was shot digital. I don’t think that the soul of movies is technology. More importantly, it's about what emotions are put inside.

Pretty pictures are tempting but then they become hollow. We see so many of those.

So what’s more important for a cinematographer: the narrative or beautiful pictures?

The narrative is just so much more profound. Pretty pictures are tempting but then they become hollow. We see so many of those, if you watch Netflix all the shows are well crafted. But not all of them get to you. I think that cinema always should come from the story. There’s a chance that people will remember a film for years, maybe even longer.

And what is your favorite thing about your job?

That you create something with a group of wonderful people. I just love that we come together, once the job is done you have a powerful and beautiful product out there that has its own life. It’s always magical to me.

You’re talking about relationships with people on set. Tell me more about your first meeting with George Clooney.

First time I worked with George as a director on Catch 22. It was when one of his regular coworkers wasn't available. George is a guy who loves to work with people more than once, he has a regular group of coworkers and then all of these people become members of his film family in a way. In 2018 I got a call from him and Grant Heslov. When they asked me to do the Catch I said "yes" immediately. Is great to work with George. He is a really visual director who knows what exactly he wants to see, who deeply understands every visual aspect of the story, and who also takes risks. He loves his actors and he's very much approaching the scenes from the actors' point of view. And also he creates great flow on the set. George likes to move really fast. I love it because everybody feels comfortable and has energy, actors feel safe and they don’t have to wait for hours for the next shot.

You continued working together on his next movie called The Midnight Sky, an ambitious sci-fi epic for Netflix. It’s a very different story from anything you've ever done before.

Of course, it was much more complex than the stuff I did before. There’s a lot of technically more complicated things to shoot: astronauts in space, zero gravity scenes, we also were shooting in real ice storms in Iceland with 16mm cameras. It was also the complex VFX work which also needed collaboration between all the departments. But I love that mix of challenges in cinema. After Control I did The Countess, a 16th-century historical drama directed by Julie Delpy, and then an action-thriller movie Harry Brown. And also western called The Keeping Room. I love that we can create all those different worlds.

The Midnight Sky is about a world-ending ecological disaster. Ever asked yourself about our future, the future of the human race?

I kept asking that question. What is going to happen 30 years from now? How does the future look like? But I have no answer, we’ll see what happens. Newspapers live on bad news but I think there is also a lot of good news around us. Let’s see how many people died of famine 20 years ago, how many girls had the chance to go to school globally then. Now compare that with the situation nowadays. That’s a lot of positive things happening. It's incredibly positive that we have had vaccines since one year after the coronavirus pandemic. Of course, we’ve still got so much to do, we should take moral responsibility for our planet and future generations. But I believe that we’re still fighting for these positive changes.

Have you got any future projects lined up?

We're just finishing work on The Tender Bar, George's new film. The situation was complicated by the pandemic – I needed a special visa to come to the States because we were shooting in Boston, my family couldn’t come to visit me there. For the first time on the set, I couldn’t see all the faces. Everyone was wearing masks, which made communication difficult, and the atmosphere around was quite strange. But we did it. I would hope that each of us will be vaccinated in the near future. However, I cannot reveal too much about my further projects. I don’t know the details myself yet. I talked to George about his next film, probably we'll start working on something bigger next year. And again – it will be a completely different subject, and journey into a completely different, new world.

see also

- Andiamo directors | Collaborative process is in the DNA of our relationship

Papaya Rocks Film Festival

Papaya Rocks Film FestivalPeople

Andiamo directors | Collaborative process is in the DNA of our relationship

- The Genius Face of Film Memes

People

The Genius Face of Film Memes

- Funded by Bill Gates, Company Develops Technology to Help Wean Mankind Off Fossil Fuels

News

Funded by Bill Gates, Company Develops Technology to Help Wean Mankind Off Fossil Fuels

- Time to Play a Game—the Biggest Announcements from This Year’s E3

Trends

Time to Play a Game—the Biggest Announcements from This Year’s E3

discover playlists

-

filmy

01

01filmy

-

Martin Scorsese

03

03Martin Scorsese

-

Papaya Young Directors 5 Autorytety

12

12Papaya Young Directors 5 Autorytety

-

Papaya Young Directors 6 #pydmastertalks

16

16Papaya Young Directors 6 #pydmastertalks