Damon Krukowski | Time is Flexible09.05.2019

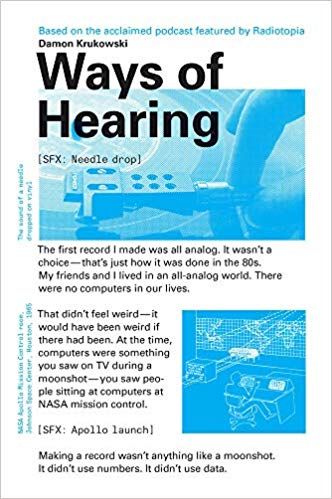

We present an excerpt from Ways of Hearing by Damon Krukowski. In this book, based on a six-part podcast, a writer-musician examines how the switch from analog to digital audio is changing our perceptions of time, space, love, money, and power.

The first record I made was all analog. It wasn’t a choice – that’s just how it was done in the 80s. My friends and I lived in an all-analog world. There were no computers in our lives. That didn’t feel weird – it would have been weird if there had been. At the time, computers were something you saw on TV during a moonshot – you saw people sitting at computers at NASA Mission Control.

Making a record wasn’t anything like a moonshot. It didn’t use numbers. It didn’t use data. Not that there was no technology involved – the tape decks, mixing board, microphones – they all seemed very magical. But they were made of magnets, gears, motors, electricity… like all the mechanical objects in our lives then. And so my bandmates and I set up our instruments in the studio. We counted off. And we played our songs. In many ways, it’s simply nostalgia to think that it was so different. [...] There’s something particular about that analog experience, which seems hard to conjure back up in the digital present – and for that very reason it feels important to try. In that analog studio, there was a feeling when the tape started rolling that this was the moment we would capture – a feeling of time moving both more slowly, and more quickly than usual. Like when you’re in an accident. Each split second is suddenly so palpable, as if you’re living in slow motion. Yet what do we say when it’s over? It all happened in an instant.

Analog recording is like an accident in other ways. On tape, there was no “undo.” You could try again, if you had the time and money. But you couldn’t move backwards. [...] Today, life as a musician is very different. In the digital studio – and I am using one now – everything you do is provisional. That is, it can be redone, reshaped, rebuilt. There’s no commitment, because each element of a recording can be endlessly changed – it can even be conjured from digital scratch, as it were, and entered into a computer directly as data, without anyone performing at all. [...]

Musicians know time is flexible. Classical players call this tempo rubato, Italian for “stolen time”. You steal a bit here, give a bit back there. Jazz players call it swing. Rock and funk players call it groove. This flexibility of time is something we’re all familiar with, whether or not we play an instrument. [...] What musicians’ terms like rubato, swing, and groove acknowledge is that time is experienced, not counted like a clock. And our experience of time is variable – it’s always changing. Even if our eyes look at a clock and see twelve equal hours, our ears are ready to steal a bit here, give a bit back there. And the analog media we use to reproduce sound – records and tapes – reflect this variable sense of time. A time that’s elastic.

What truly changed in popular music during the 1980s was that digital machines entered the mix for the first time. And machines have a different sense of time.

The first turntables, Victrolas, were hand-cranked – you wound up a spring, which spun the platter as it wound down. The speed was hardly steady – at least never for long. At the opposite end of the 20th century, hip hop DJs used speed controls on turntables to change the tempo of a record – to match it to another and keep the groove going. Or in the studio, to pile up samples from older records and make a new one. In 1990, A Tribe Called Quest sampled the bass from Walk on the Wild Side – along with the surface noise from the LP – added it to a drum loop from a Lonnie Smith LP, and made a new hit out of it. They also had to give up on collecting any royalties.

Ali Shaheed Muhammad: One of the biggest samples that we were able to clear was “Walk on the Wild Side” by Lou Reed. And by clearing that, he just took 100% of that song.

Frannie Kelley: Wait. Really?

Ali Shaheed Muhammad: He did.

Frannie Kelley: You’re saying Lou Reed gets 100% of the publishing?

That’s Ali Shaheed Muhammad, from A Tribe Called Quest, and Frannie Kelley— they host a podcast about hip hop called Microphone Check. (Damon Krukowski was a guest on their show – ed. note)

Ali Shaheed Muhammad: Yeah. That’s his song.

Damon Krukowski: Ali I always thought, you know my band Galaxie 500, we ripped off the Velvet Underground way more than you did! And we didn’t have to pay them a dime.

I asked Ali how Tribe used the variable speed of turntables to make their own records.

Ali Shaheed Muhammad: You know, sometimes we would change the speed on a turntable, because the staple hip hop turntable is the Technics 1200 – so that has a pitch control, and we would sometimes pitch it high there. Sometimes a 33 rpm record, you put it on 45. And one thing with Tribe – we layered certain sounds and so you kind of had to pitch them, cause often they weren’t in the same key.

Layering these sounds, A Tribe Called Quest discovered something else about their samples.

Ali Shaheed Muhammad: The records we were recording – they might not have been playing to a metronome, and they were free-flowing, so there are moments within, let’s say, even a two-bar phrase, that maybe a drummer or bass player like were aligned in the first two bars and the tempo seemed to be consistent. And then the last three beats of a bar it sped up, or slowed down.

In 1988, the songs my bandmates and I recorded slowed down and sped up, just like Ali Shaheed described. I know, because I was the drummer. We played as steadily as we could – but this was a performance. [...] You might find that a flaw in our recordings. Or you might feel it’s a part of their charm. [...]

Our experience of time is flexible. But not long after we recorded that first Galaxie 500 album, the commercial music world for the most part decided that this was most definitely a flaw. Bands on major labels – even bands who came out of our DIY, indie scene – started recording to a “click track.” That is, a metronome.

Fashions in music come and go – at the time, everyone was also using the swirling effect called a “flanger”. No one remembers why. But the click track proved more than a fad – it was a change that stuck. Because what truly changed in popular music during the 1980s was that digital machines entered the mix for the first time. And machines have a different sense of time. [...]

Excerpted and adapted from Ways of Hearing by Damon Krukowski (The MIT Press, 2019).

see also

- Naomi Watts Joins Game of Thrones Prequel Cast

News

Naomi Watts Joins Game of Thrones Prequel Cast

- Iza Aleksandrowicz, Kiyong Maeng: Inspiration is where the popular beliefs die

Papaya Young Directors

Papaya Young DirectorsPeople

Iza Aleksandrowicz, Kiyong Maeng: Inspiration is where the popular beliefs die

- Toto’s Africa to Play on an Endless Loop at a Desert Installation

News

Toto’s Africa to Play on an Endless Loop at a Desert Installation

- Andrea Marini: Responsibility towards the audience

People

Andrea Marini: Responsibility towards the audience

discover playlists

-

Papaya Young Directors 5 Autorytety

12

12Papaya Young Directors 5 Autorytety

-

Instagram Stories PYD 2020

02

02Instagram Stories PYD 2020

-

David Michôd

03

03David Michôd

-

PZU

04

04PZU