Instagram reality

06.12.2019

With dozens of apps and AR filters you can use to nip, tuck, squeeze, and fine-tune your selfie, the subliminal pressure to be “perfect” is no longer subliminal. Increasingly there is a worrying blur between Instagram vs. Reality, and one of the newer side effects of social media is the growing trend of cosmetic surgery. As we strive to get that filtered look IRL, what kind of implications does this have for our humanness?

Growing up in Midwestern America, I was raised on an unhealthy amount of celebrity culture, which stood in polar opposition to our small, boring suburban life. From tabloids to glossy mags, I remember being inundated with headlines of nips and tucks (and botches), who lost weight (and who gained it), who wore it best (or worse, just “who?”). Looking perfect was a luxury only a few could afford, and a goal for everyone else.

By the time I went away to college, you could download a bootleg copy of Photoshop to retouch your MySpace photos. And after that, smartphones brought celebrity culture into our pockets, instantly.

In the early 2000s, I was in high school where reality TV became a thing, catapulting average people into pseudo-celebrity and making rich kids like Paris Hilton and Kim Kardashian famous for being, well, famous. By the time I went away to college, you could download a bootleg copy of Photoshop to retouch your MySpace photos. And at the turn of the new decade, smartphones brought celebrity culture into our pockets, instantly.

A confluence of all these things—high beauty standards and the pressure to conform, an obsession with fame, reality TV simultaneously glorifying and demystifying plastic surgery, technology becoming more accessible and cheaper, the smartphone and social media, and many more—has evolved celebrity culture into selfie culture. Technology has become ever more intimate and intermingled with our identities and bodies, and just like in all aspects of our lives, it blurs the line between digital and physical.

Filters blur the line between reality and fantasy, creating unrealistic expectations of what can be done with plastic surgery.

The rise of the selfie has made us much more self-conscious, self-critical and self-aware, putting pressure on people to be selfie-perfect. Photo-editing apps like Facetune and face filters in Instagram and Snapchat “offer a degree of image control that was previously only available to celebrities or models,” says Dr. Neelam Vashi, author of Selfies—Living in the Era of Filtered Photographs. The filters that slim your face, smooth your skin, and pout your lips mimic procedures like fillers, nose jobs, brow lifts, and Botox. Since 2000, cosmetic surgery procedures have increased by 137% according to a report by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, with young people contributing to the rise significantly.

Filters blur the line between reality and fantasy, creating unrealistic expectations of what can be done with plastic surgery. New beauty norms propagated through social media, like “Instagram Face,” have contributed to the rise of new phenomena such as “Snapchat dysmorphia,” a body-image disorder characterized by the need to heavily edit one's own digital image. "I can easily accept not looking like a celebrity, but it's much harder for me to accept that I can't look like an enhanced version of myself from a social media filter," Vashi said.

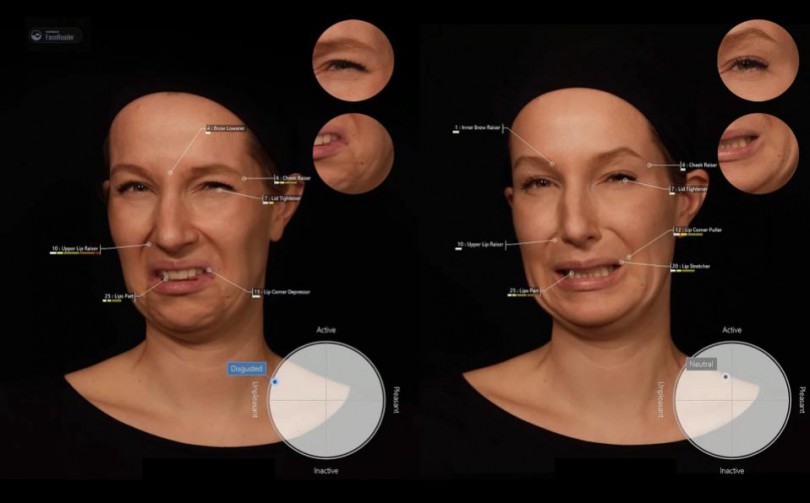

At Dutch Design Week in October, I met design researcher and cosmetic doctor Marsha Wichers. In her project Face Design, she explores the effect of facial enhancement on the human condition. “Our face is one of the most important parts of what makes us human and embodies our personality and individuality.” Using her own face, Wichers designed AI software to identify emotions through facial expressions before and after Botox injections.

She found there’s a delicate balance to cosmetic surgery, and if taken to extremes, faces will begin to look unnatural, having implications for the way we communicate. For example, the expression for “Disgusted” in which normally the corners of the mouth are depressed was interpreted as “Neutral” by the computer in the presence of Botox. It’s a great speculative design project exploring the relationship between online editing and offline "enhancements" that left me with more questions than answers, such as: does cosmetic surgery affect the limits of AI? With beauty standards becoming homogenized and ubiquitous, how does this impact emerging technologies like facial recognition? On a human level, will we understand one another if we can no longer fully utilize our facial expressions?

Until we’re all living behind our screens as digital avatars in a Wall-E type of world, there’s still a hard line between expectation—the pixel-perfect, finely-tuned digital images we’ve created—versus reality. The issue goes way beyond just the use of filters, but instead to the ideals and norms that platforms like Instagram and Snapchat have introduced into our lives. The larger conversation to be had is about how our conception of beauty is constructed, upheld, and relentlessly emphasized, and the broader ethical and societal implications of that.

see also

- No-Drama Vacation. Robert De Niro and Roger Federer in a Switzerland Tourism Ad

News

No-Drama Vacation. Robert De Niro and Roger Federer in a Switzerland Tourism Ad

- Medicine, Food, Poison. The Marvelous World of Fungi Explored in Upcoming Documentary

News

Medicine, Food, Poison. The Marvelous World of Fungi Explored in Upcoming Documentary

- Environmentally-Friendly School to Receive Prestigious RIBA Award

News

Environmentally-Friendly School to Receive Prestigious RIBA Award

- Fourth Season of "Stranger Things" to Be One of the Most Expensive in Television History, With $30M Spent per Episode

News

Fourth Season of "Stranger Things" to Be One of the Most Expensive in Television History, With $30M Spent per Episode

discover playlists

-

Paul Thomas Anderson

02

02Paul Thomas Anderson

-

PYD: Music Stories

07

07PYD: Music Stories

-

filmy

01

01filmy

-

Domowe koncerty Global Citizen One World: Together at Home

13

13Domowe koncerty Global Citizen One World: Together at Home