Submissions for this year’s Papaya Young Directors competition are still open, but the window closes on March 14. There’s little time left, so if you have an interesting idea for a commercial or a music video and have faith in your own skillset, you can still apply. The ten screenwriters listed below have proven that no deadline will stop a passionate storyteller capable of creatively reworking their own thoughts and experiences. Do your best and try to follow in their footsteps!

Taxi Driver, directed by Martin Scorsese, written by Paul Schrader, 1976

Less than two weeks. That’s how long it took Schrader, then twenty-six, to paint his portrait of one of the most complex characters in the history of American filmmaking. Within those fourteen days, Schrader even wrote two version of his screenplay, one after the other, and poured much of his view and reading of the world around him into Travis Bickle. At the time, the screenwriter, already a writer and promising film critic, was in what he himself called “a bad place.” He was deep in debt, had burned most of the bridges in the industry, and fared poorly with women. He lived out of a suitcase for a couple of weeks, and drove around Los Angeles in a car he also spent most nights in, ate junk food, and visited porno theaters. It was only after he finally landed in a hospital that he realized how profoundly alone he had been, despite being constantly surrounded by people. Writing the screenplay for Taxi Driver was, in a way, like therapy for him, as it allowed him to pour all of his sorrows and grievances out onto paper.

Ferris Bueller's Day Off, written and directed by John Hughes, 1986

Sometimes, you just have to dig deep and muster up whatever energy left you have inside to make the deadline. And when the deadline is set by the rapidly approaching Writers Guild of America strike, bound to halt all film production industry-wide, there’s just no time left to waste, is there? After starting out as a copywriter at an ad agency, John Hughes became famous for the ease with which he rendered his thoughts into scriptwork. Whenever he began working on a new script, he entered into a peculiar trance, writing up to twenty hours at a time, completing anywhere between 20 and 30 pages of text. That’s exactly how he wrote Ferris Bueller's Day Off, the now cult classic about a clever teenager going through the struggles of growing up in his very own way, Hughes wrote the first draft in barely six days and made very little rewrites before shooting it. To make the final cut of the film, the editor threw out over an hour of footage.

Scream, directed by Wes Craven, written by Kevin Williamson, 1996

There’s no better motivation for a beginner screenwriter than money, a fact that Kevin Williamson learned the hard way a couple of years after moving to Los Angeles, when he was ready to give up his ambition and dreams of writing original horror novels. Although his screenplay for Killing Mrs. Tingle found a buyer, nothing suggested that anyone was planning to turn it into a hit movie (it was eventually brought to the screen by Williamson himself in 1999), and his predicament was growing serious by the day. So he sealed himself up in his living room for the weekend and poured all his ideas about a group of young people with expert knowledge of the horror and thriller finding themselves the target of a serial killer down onto paper. Within those three days, Williamson penned not only the first draft of the script for Scream, but the outlines for the sequel and threequel, too. The studio ultimately passed on the third installment, but his weekend’s work ended up making Williamson a household name in horror film in the late 1990s.

Barton Fink, written and directed by Joel and Ethan Coen, 1991

Sometimes, writing just doesn’t come easy, regardless of intention, the preferred method for achieving deep focus, or brainstorming sessions intended to spark whatever creativity is left within us. If you ever find yourself in a similar situation, try to put whatever you’re working on aside and start writing something in a similar vein. That’s how the Coen brothers once famously overcame their writers block. Working on Miller’s Crossing, they suddenly found themselves stuck and could not move their story forward. So they took three weeks off and in that time came up with a story about a screenwriter struggling with writer’s block and tormented by his own increasingly desperate mind. Today, Barton Fink is considered one of the most brilliant scripts of the 1990s, while the film itself went on to win the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. Curiously, the inspiration for Big Lebowski, another successful movie the brotherly duo made in the ‘90s, struck the Coens when they were writing Barton Fink. One film, a variety of uses.

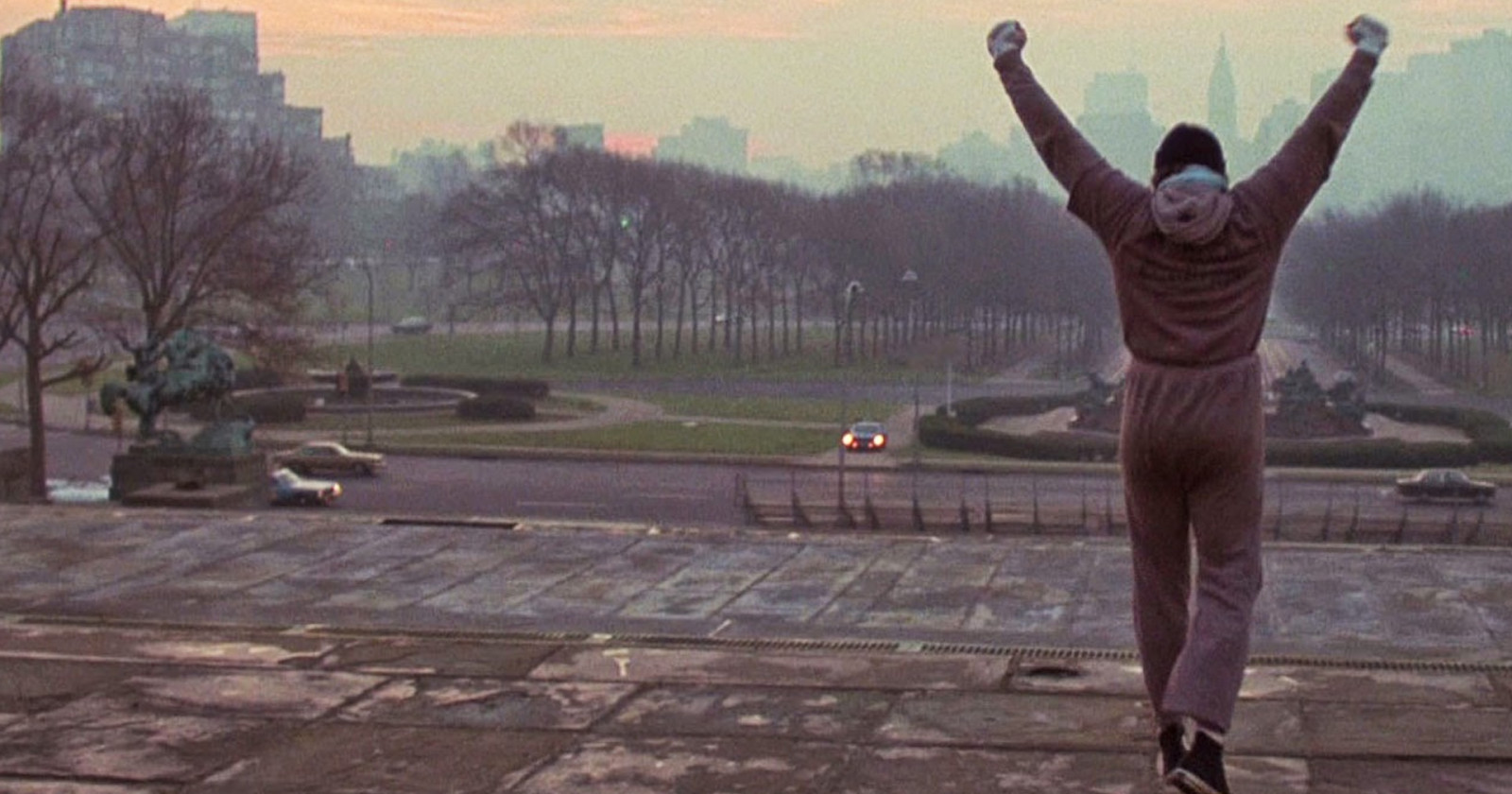

Rocky, directed by John G. Avildsen, written by Sylvester Stallone, 1976

The script for Rocky is the stuff of legend. Unable to land parts for himself and fast approaching bankruptcy, Stallone decided to write a film he could star in. He struggled with the script, however, until one day he saw Muhammad Ali stumble his way through fifteen rounds against Chuck Wepner. The image grew into a classic underdog story, which saw an ambitious boxer flittering his talent away working as a local mob enforcer just to make ends meet, whose world gets turned upside down when he finally gets a shot at a title fight. Although fleshing the idea out took some time, when he finally had the storyline down Stallone finished the ninety-page-long script in a little over three days. Then, despite being broke, he waited out a lot of Hollywood big wigs who offered him a lot of money for the script on the condition that someone else played the title role. And history proved him right—soon after its release, Rocky absolutely knocked out the worldwide box office.

Magnolia, written and directed by Paul Thomas Anderson, 1999

How do you write a three-hour-long movie about people looking for happiness and the meaning of life and give every character equal amount of meaningful dialogue, make them ambiguous enough to subvert quick judgments, and have each one offer the audience a different sort of reflection? Well, by creating a complex system of mutually interlocking scenes bordering on melodrama and psychological drama. Paul Thomas Anderson began developing Magnolia back during the overlong postproduction of Boogie Nights, and the whole process took up quite some time, as he initially wanted to pen a modest project that wouldn’t require significant investment, but the film’s scope continued to grow as the director kept coming up with new ideas. The main draft of the script, however, was put to paper within more or less two weeks, which Anderson spent sealed up in a cabin owned by William H. Macy. Anderson avoided leaving the place for fear of being bit by a snake he once saw nearby, and the fear quickly became one of his key inspirations.

Basic Instinct, directed by Paul Verhoeven, written by Joe Eszterhas, 1991

Hollywood tends to mangle screenwriter ideas so deeply that although they receive a writing credit for their work, they often have to sacrifice much more than money to protect their beloved projects from allegedly necessary changes. This was the experience of Joe Eszterhas, who spent a lot of time trying to sell his script for a psychological thriller about a detective tangled up in an affair with a femme fatale suspect in a murder investigation—so much so that he kept trying to impress prospective buyers by telling them that he worked on it for years. When he learned that the director and the producers wanted to punch up the sexual aspect of the story, Eszterhas left the project without a second thought, but not before thoroughly lambasting Verhoeven and his partners in crime. And in the end, he emerged victorious—after the director agreed with him and the two reconciled, Eszterhas came back on board as an executive producer and reclaimed control over any changes made to the script.

Sex, Lies, and Videotape, written and directed by Steven Soderbergh, 1989

In a sense, it’s another legendary script, as Sex, Lies, and Videotape, after receiving the Palme d’Or at Cannes, an Academy Award nomination for Best Screenplay, and a dozen other awards and honors, became a catalyst for the emergence of what has come to be knowns as the new American independent cinema. The film is an excellent, incredibly mature, and emotionally complex exploration of human sexuality, the need for intimacy, and the thin line between love and mere satisfaction of deep-seated urges. Conceived in the mind of a twenty-six-year-old filmmaker, this screenwriting and directing debut, drawing extensively on his own experiences, came together within eight days as he drove across the United States. Although Soderbergh later confessed that he would never again write in such a rush, he acquired a reputation for fast-paced work, whether as a writer or behind the camera. Proof? During the 2020 lockdown, Soderbergh managed to write three screenplays, including… a Sex, Lies, and Videotape sequel.

Do the Right Thing, written and directed by Spike Lee, 1989

The premiere of Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, a story of a culturally, socially, and economically diverse group of Brooklyn residents, marked another turning point in the trajectory of American independent cinema. Lee, who produced, wrote, directed, and starred in the film, undertook to perform a vivisection of Americanness founded upon psychological and racial violence that ultimately proved so disturbing that if it weren’t for the support from Universal, the film might have never seen the light of day. For Lee, the screenplay, initially titled Heat Wave, was a profoundly personal project, not only because it interrogated the many racial tensions of the 1980s, but because it also drew considerably on his own personal experience of growing up in the Brooklyn projects. It should come as no surprise, then, that he wrote the script in two weeks, starting his day only after pouring the jumble of ideas and emotions down he woke up with onto paper.

End of Watch, written and directed by David Ayer, 2012

The script for End of Watch was another personal project. While David Ayer built a reputation in the industry as the go-to guy for gritty cop dramas (the Ayer-written Training Day brought Denzel Washington an Academy Award), he eventually found himself tired of telling stories about tough, corrupt cops. Instead, he wanted to shoot a film about the bonds of police brotherhood, loyalty, and friendship. With the story already fleshed out in his head, he penned the script for End of Watch, a quasi-documentary feature film about cops trying to protect and serve on the streets of South Los Angeles, in just six days. Ayer knew the area well, because he grew up there and still had friends in the district’s police department, so he incorporated the truth of the streets into his characters’ fictional biographies and then shot much of the film on real-life locations, paying a bittersweet homage to the people he’s always admired. Although he has since returned to the cop drama genre, none of the newer entries were ever so personal.

see also

- Nearly 200 Titles from Around the World. The 2021 Papaya Rocks Film Festival Kicks Off

Papaya Rocks Film Festival

Papaya Rocks Film FestivalNews

Nearly 200 Titles from Around the World. The 2021 Papaya Rocks Film Festival Kicks Off

- Mick Champayne | Can AI Be Creative?

Trends

Mick Champayne | Can AI Be Creative?

- James Bearded Sustainable Seafood

Trends

James Bearded Sustainable Seafood

- Chris Duffey | About Aimé – the co-author of Superhuman Innovation

Opinions

Chris Duffey | About Aimé – the co-author of Superhuman Innovation

discover playlists

-

Muzeum Van Gogha w 4K

06

06Muzeum Van Gogha w 4K

-

John Peel Sessions

17

17John Peel Sessions

-

George Lucas

02

02George Lucas

-

Music Stories PYD 2020

02

02Music Stories PYD 2020