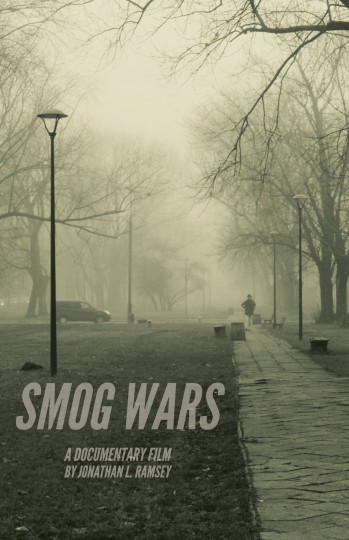

"Smog Wars": The Smell of Winter20.10.2018

The question of smog and air pollution comes back every year with ever greater force. From early fall to late winter, millions of Poles have to find ways of navigating the choking plume that smothers the land. Who is responsible for this sad state of affairs? What can we do to reverse it? Why is it so hard to come up with a comprehensive solution? We speak with Michał Konopa, a producer who team up with writer and director Jonathan L. Ramsey to develop Smog Wars, the first full-length documentary investigating the problem of air pollution in Poland.

Why make a film like that?

Michał Konopa: We were compelled by inner necessity, I guess—my son, Kazio, has asthma and Jonathan had just welcomed a child. I remember that one day the two of us we were sitting twenty floors above the ground and looking out at the city, blanketed with a thick, gray, smothering fog. We thought that we had to so something, we had to make people realize that this is no way to live. That the problem, setting us back entire decades, was so sweeping and so multifaceted that no single government or local government can easily remedy it, that it needs to be tackled at every level from the ground up. Each one of us will have to contribute in order to scale the problem down.

You mentioned children.

My son was born in Krakow. Our interviews with doctors revealed that the first trimester is critical when it comes to the development of asthma or allergies in children. In my son’s case, these first three months were December, January, and February—peak smog season. My other son was also born in Krakow, but he was conceived in April and he’s the picture of health. We had no idea of any of these things when we were thinking about having children. And people thinking about starting families should definitely take this into account, especially if they live in places where air pollution is a problem. I also mentioned children for another reason—I believe it’s much easier to develop pro-environmental attitudes and sensibilities in younger generations. It makes me very glad when I hear children police harmful adult behaviors: “Stop heating the house with plastic bottles and old shoes, it’s making me sick.”

How did smog make such a comeback in our collective consciousness? It’s not a new development by any measure and yet the public opinion has only come around to making it an issue just recently.

We just started measuring it. The same thing happened with illiteracy—at some point, someone realized that it’s important everyone be able to read, so they started measuring the literacy rate and doing something to boost it. It’s the same with air pollution—we realized the extent of the problem because a lot of people suddenly took up measuring it. The World Health Organization publishes air quality reports and guidelines annually, and Polish norms and guidelines are much less restrictive than WHO’s. One of the people we interviewed for the documentary said that she’s been familiar with the odor of smog since childhood, but that all her life she thought that this was simply how winter air smelled.

Smog Wars is about Warsaw. But isn’t Krakow the smog capital of Poland?

Warsaw is featured as an example: this is what it’s like here, but the situation in your city may not be that different. Proportions, however, are definitely different, because 60% of annual pollution in Warsaw comes from cars. Additionally, in contrast to Krakow, Warsaw is much better off in terms of both location and city layout. Krakow is built out in rings, so the city’s poorly ventilated and its location at the bottom of a valley make it a prime spot for fog and particulate air pollution to accumulate. Warsaw, on the other hand, has a grid-based layout and sits on a plain. There’s the sprawling Kampinos Forest to the northwest of the city and the Vistula is much broader here than it is in Krakow—all of these improve air quality and help filter it out. This puts it in a much better spot than Krakow, but it’s the latter that has better-developed anti-smog policies. The city authorities there are much more efficient—the local grant system will pay for your new heating unit, but in Warsaw you have to buy it yourself and then apply to the city to reimburse you for 80% of the cost. For the majority of people who should have their home heating units replaced, paying 15,000 PLN out of pocket is out of the question. Warsaw also has around 10,000 community housing units—their tenants have no say in what’s used to heat their homes and can’t simply swap out their masonry heater for a gas-fed unit.

You said you wanted your movie distributed worldwide — through international streaming platforms, for example. I can already see the skeptics screaming their heads off that portraying our country as a trash-burning backwater is idiotic.

When someone calls you lazy, denial is usually your first reaction. But as time goes by, you often realize that you could be doing more. That’s what we’re hoping for here. We’re not saying that Poland has the worst smog problem in the world, it doesn’t. But the problem is here and we’re most definitely not tackling it as seriously as we should be. And it’s going to take time. It’s like with sorting waste—you can’t expect the system to run smoothly six or twelve months after it’s introduced. It needs a long-term education effort, you need to hear about sorting waste and sort it since childhood, you need to understand why sorting is worth it in the long run. Everyone should be made to see the kilometer-long patches of garbage traversing the oceans. Together, these efforts end up forming an additional layer of environmental consciousness and new, positive habits and attitudes. The same approach will work for improving air quality. It’s easy say: “It doesn’t matter whether I choose a car or public transportation, because fifty or a hundred thousand other people will still choose their cars.” You hear the same sentiment with regard to elections: “What can my vote possibly change if there are thirty million people in Poland with the right to vote?” But we live in communities, and the world we live in is, more or less, the sum of our individual decisions.

Who did you interview for the film? I was surprised by the appearance of a clergyman who considers contributing to the deterioration of air quality a sin.

We spoke with a group of environmental activists fighting against air pollution, with doctors about the terrible toll that smog exacts on our bodies. We interviewed a lawyer who claims that we can sue the authorities for negligence and a scientist who calculated the staggering human, economic, and healthcare costs of smog in Poland. Did you know that smog-related illnesses result in a total nationwide workday loss rate of fifteen million days per year? The interview with the head of a company selling air pollution masks, air purifiers, and air filters. On the one hand, their products allow us to shield ourselves from smog, but on the other air pollution keeps it in business. We also interviewed a Franciscan friar you mentioned, who founded a local environmental organization, and an entrepreneur working in the floral industry whose greenhouse heating systems emit 120 tons of carbon into the atmosphere each year. We spoke with cab drivers who reduce emissions by decreasing the number of cars people take out onto the road, but nevertheless still contribute to the menace of air pollution by using cars with internal combustion engines. We also interviewed ordinary people, parents, and Warsaw locals.

Jonathan Ramsey, the director, is American. Do you think that his outside perspective helped here?

Most definitely. Jonny perceives reality much differently than any other Warsaw local. It’s rooted in a different approach to communication and messaging—Americans tend to emphasize the problem and look for different perspectives, whereas the Polish approach is much more unilateral and shallow. With our film, we tried to avoid the quintessentially Polish search for the guilty party and instead tried to work the problem and look for solutions. Plus, Jonathan’s been living in Poland for the past eight years now, so when an eighty-year-old granny tells him that she doesn’t have money for anything other than coal then he gets where she’s coming from. A director with no experience living in Poland would probably have some difficulty understanding that.

Smog Wars will be screened on October 27 at the Luna cinema in Warsaw and on October 29 at the Centrum Cinema in Toruń.

see also

- Logic, Bobby Tarantino or Young Sinatra?

People

Logic, Bobby Tarantino or Young Sinatra?

- Could your pre-schooler learn to code?

Opinions

Could your pre-schooler learn to code?

- Eduard Micu: Things that make us laugh

Papaya Young Directors

Papaya Young DirectorsPeople

Eduard Micu: Things that make us laugh

- Are You a Super Recognizer? Take The Quiz Devised by Australian Researchers to Find Out

News

Are You a Super Recognizer? Take The Quiz Devised by Australian Researchers to Find Out

discover playlists

-

Papaya Young Directors 6 #pydmastertalks

16

16Papaya Young Directors 6 #pydmastertalks

-

Nagrody Specjalne PYD 2020

02

02Nagrody Specjalne PYD 2020

-

Domowe koncerty Global Citizen One World: Together at Home

13

13Domowe koncerty Global Citizen One World: Together at Home

-

05

05